13 maggio: perché gli afro-brasiliani non commemorano l’abolizione dalla schiavitù

di Patricia Alexandre da Silva e Stefano Raschietti

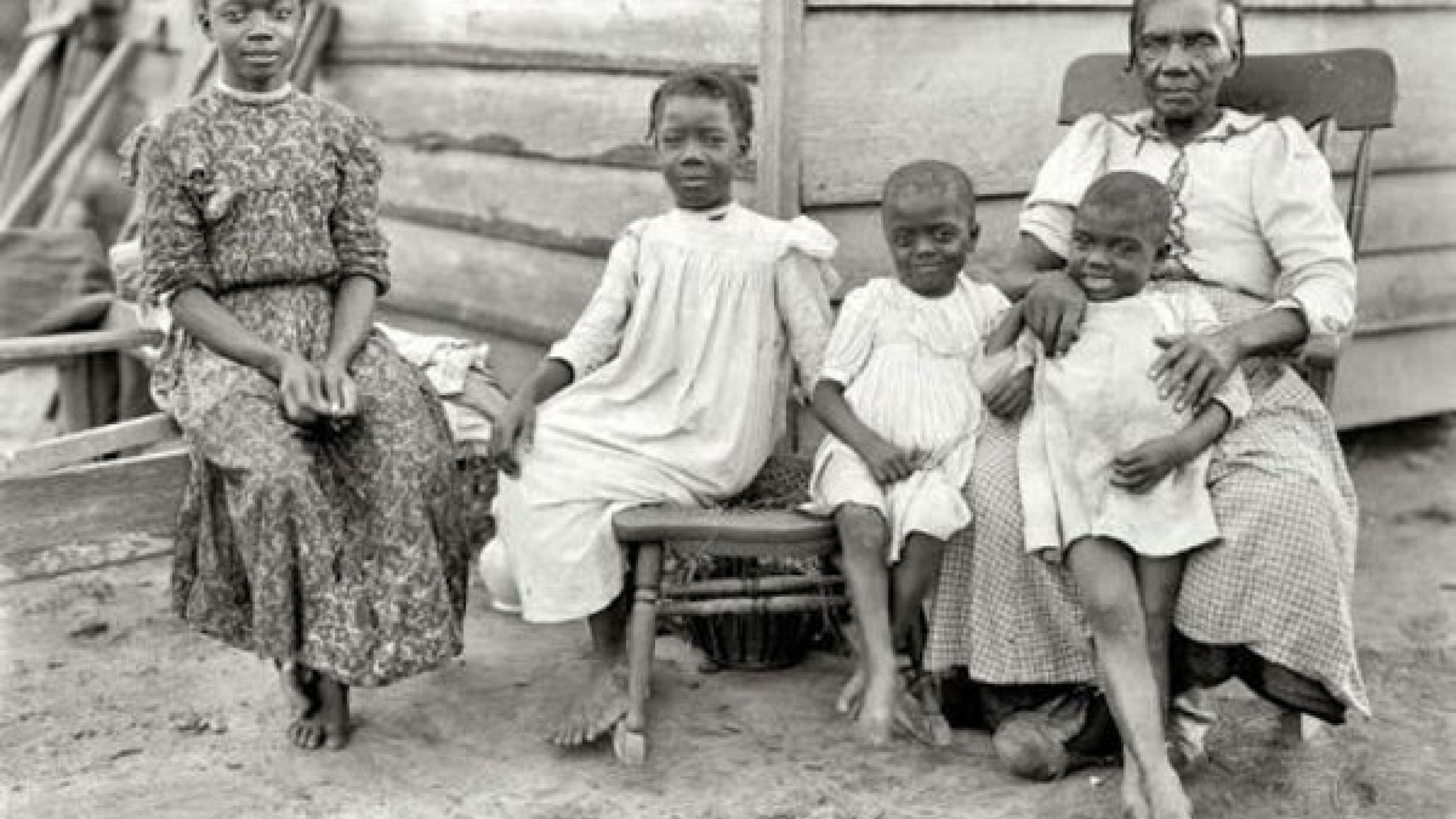

Il Brasile fu l'ultimo paese indipendente delle Americhe, con la cosidetta Lei Áurea (“Legge d'Oro”), promulgata il 13 maggio 1888, 129 anni fá, ad abolire la schiavitù per i discendenti degli africani. L’editto fu firmato dalla Principessa Isabel, figlia dell'imperatore del Brasile Dom Pedro II, mentre il padre era in viaggio all’estero (la monarchia portoghese in Brasile durerà fino al 1889). Ma i neri non commemorano affato questa data. Vediamo il perchè.

L'abolizione della schiavitù fu il risultato di un lungo processo di natura politica, economica e sociale. Prima della Legge d'Oro, altre tre leggi avevano cominciato a rendere più difficile il commercio e il mantenimento del lavoro degli schiavi nel paese.

Nel 1850, fu approvata la Legge Eusébio de Queiroz che proibiva il commercio internazionale degli schiavi. Diminuiva cosí la quantità di schiavi sul mercato e la "merce" diventava molto più costosa. Vent’anni dopo, nel 1871, quelli nati dopo questa data, con la Legge del Ventre Libero si rendevano automaticamente liberi i figli degli schiavi. Nel 1885, la Legge Saraiva-Cotegipe, conosciuta anche come Legge dei Sessantenni, abrogava lo stato di schiavitù agli afro-brasiliani con più di 65 anni.

Questi primi passi per l’abolizione definitiva della schiavitù furono dovuti a una forte pressione inglese. Le ragioni non erano umanitarie, ma prettamente economiche. All´Inghilterra, potenza industriale dell’800, interessava espandere il mercato in Brasile e, di conseguenza, aveva bisogno di convertire gli schiavi in manodopera salariata.

Parallelamente alla riduzione del numero degli schiavi, nelle piantagioni di caffè, vi fu l’aumento dell’immigrazione europea. Per i grandi fazendeiros cominciava a divenire più economica e redditizia la manodopera degli immigrati. Era abbondante e a buon mercato, più del lavoro degli schiavi.

Tutto questo avveniva contemporaneamente al sorgere del movimento abolizionista e alla resistenza della popolazione nera, che si ribellava e fuggiva per formare i famosi quilombos (comunità rurali di discendenti africani). Nel 1887, l'esercito locale aveva smesso di catturare schiavi fuggiaschi per restituirli ai fazendeiros. Nel 1888, il censimento dell'Impero mostrava che solo il 15% della popolazione nera rimaneva in stato di schiavitù. Questo anche grazie al grande numero di schiavi che si affrancava comprando la propria libertà.

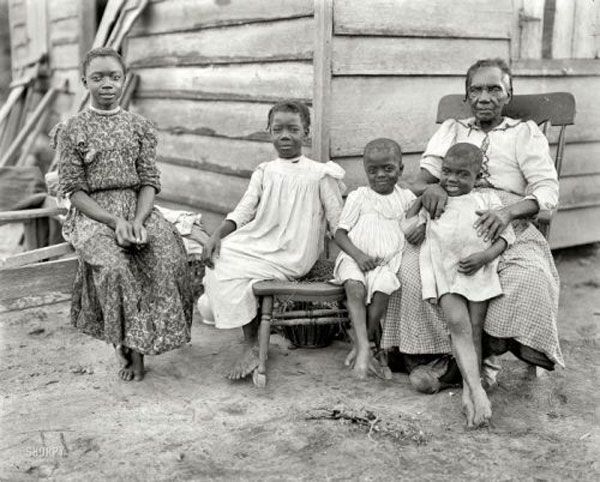

In questo contesto, la promulgazione della Legge d'Oro arrivava – in ritardo – a riconoscere un dato di fatto. Ma quello che é più importante constatare é che dopo l'abolizione della schiavitù, non é stata presa nessuna misura per inserire la popolazione nera nella società brasiliana. Non ci fu nessuna procedura per facilitare l'accesso degli afro-brasiliani al mercato del lavoro e all’acquisto della terra, della casa o di altre proprietà. Nascevano cosí le favelas: occupazioni abusive di aree periferiche, costruzioni di abitazioni precarie e sviluppo di mercati informali. I liberti erano lasciati ai margini anche delle politiche sanitarie ed educative. Di fatto si impediva loro di esercitare il pieno diritto alla cittadinanza.

129 anni sono passati e le relazioni razziali asimmetriche continuano a sussistere, con strati popolari prevalentemente formati da neri, condannati all'esclusione sociale. I sondaggi delle Nazioni Unite indicano, per esempio, che il 70% delle persone che vivono in estrema povertà in Brasile sono neri e che lo stipendio medio della popolazione afro-brasiliana nel paese è di 2,4 volte inferiore a quello dei bianchi. Inoltre, l'80% dei brasiliani analfabeti sono neri e più del 40% delle vittime di omicidio nel paese sono neri tra i 15 e i 29 anni.

C'è ancora una lunga strada da percorrere. Per tutto questo, il 13 maggio per il Brasile, più che un’occasione di celebrazione, è giorno di riflessione e di coscientizzazione. L´abolizione della schiavitù non é stato un atto di benevolenza dei padroni, ma un lungo processo di lotta per la libertà. Per questo, gli afro-brasiliani preferiscono celebrare il 20 novembre, giorno della morte di Zumbi, leader del quilombo di Palmares, simbolo della resistenza nera e della lotta contro la schiavitù.

13 May: why the Afro-Brazilians do not commemorate the abolition of slavery

Patricia Alexandre da Silva and Stefano Raschietti

Brazil was the last independent country of the Americas to abolish the slavery of African descendants with the so-called Lei Áurea (“Golden Law”), which was promulgated 129 years ago, on 13 May 1888. The edict was signed by Princess Isabel, the daughter of the Emperor of Brazil, Dom Pedro II, while her father was travelling abroad (the Brazilian monarchy lasted until 1889). However the Afro-Brazilians do not commemorate this date at all and we will now explain why.

The abolition of slavery was the result of a long political, economic and social process. Before the Golden Law was promulgated, another three laws had begun to make it more difficult to maintain the slave trade.

In 1850, the Eusébio de Queiroz Law was approved, forbidding the international slave trade and thereby reducing the number of slaves on the market, with the result that the "merchandise" became much more expensive. Twenty years later, in 1871, thanks to the Law of free birth, the children of slaves born after this date were automatically freed from slavery. In 1885, the Saraiva-Cotegipe Law (also known as the Law of the Sexagenarians) abolished the slave status of Afro-Brazilians who were older than 65.

These first steps towards the definitive abolition of slavery were due to strong pressure from Great Britain. The reasons for this pressure were not humanitarian, but purely economic. Great Britain was an industrial power in the 19th century and was primarily interested in expanding the Brazilian market; consequently, it needed to convert the slaves into paid labor.

Along with the reduction in the number of the slaves, there was an increase in European immigration in the coffee plantations. The fazendeiros found that immigrant labor was more economical and profitable because it was more abundant and cheaper than the work of slaves.

As this was happening, the movement for the abolition of slavery was emerging and the black population began to rebel and escape in order to set up the famous quilombos (rural communities of African descendants). In 1887, the local army stopped capturing and returning escaped slaves to the fazendeiros. In 1888, the census of the Empire showed that only 15% of the black population were still slaves. This was also due to the fact that a great number of slaves were buying their freedom.

In this context, the promulgation of the Golden Law was actually late in recognizing an established fact. However, it is more important to remember that, after the abolition of slavery, nothing was done to insert the black population into Brazilian society. There was no procedure in place to facilitate their access to the job market, or to help them buy land, houses or other properties. Thus did the favelas spring to life: the unauthorized occupations of peripheral areas, the construction of precarious dwellings and the development of unofficial markets. The freed slaves were also denied the benefits of health and education policies. Indeed, they were prevented from exercising the full rights of citizenship.

129 years have passed and the asymmetrical racial relationships continue to exist and the working-class, mainly formed by blacks, is condemned to social exclusion. Surveys carried out by the United Nations show that 70% of people who live in extreme poverty in Brazil are black, and that the average salary of the Afro-Brazilian population is 2.4 times inferior to the salary of white people. Furthermore, 80% of illiterate Brazilians are black and more than 40% of the victims of homicide are young black men aged between 15 and 29.

There is still a long way to go. For all these reasons, rather than an occasion for celebration, 13 May in Brazil is a day for reflection and awareness. The abolition of slavery was not an act of benevolence by the slave-owners, but the result of a long struggle for freedom. This explains why Afro-Brazilians prefer to celebrate on 20 November, the day of the death of Zumbi, the leader of the quilombo of Palmares, who is a symbol of black resistance and the struggle against slavery.

Link &

Download

Accedi qui con il tuo nome utente e password per visualizzare e scaricare i file riservati.